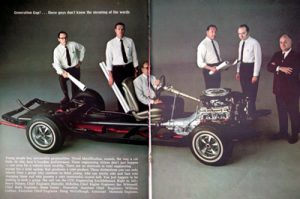

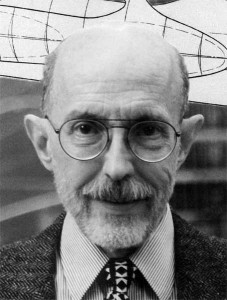

About 20 years ago, I sat down with former Pontiac Chief Designer William “Bill” Porter in New York City. Over breakfast, he discussed his role at Pontiac during the early and mid 1960s, his involvement with what became the 1968 GTO and LeMans, the 1970-81 second generation Firebird; the part he played in the creation of the 1973 Trans Am’s “screaming chicken” hood decal and the “polycast” honeycomb wheel – to mention just a few of the now-famous icons of the Pontiac Motor Division that trace their origins back to the pencil of Bill Porter.

Porter also shared his memories of former Pontiac General Manager Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen, John Z. DeLorean, Bill Mitchell, John Shettler and other names from the division’s glory days. He discussed the latter part of his career with General Motors and shared his observations on the Pontiac of today, its current styling perspective and its likely future.

Porter, who began his 40-year career with GM design in 1958, retired from General Motors in 1996. One of his final projects was the exterior shell of what became the 2000 Buick LeSabre.

Q: How did you get started at Pontiac?

In 1957, while working on a Master’s degree in Industrial Design at Pratt Institute, I was hired as a summer student by GM Styling, as it was called then. Luckily, I was invited back as a fulltime employee in 1958. I spent my first couple of years as a car designer in far-out advanced studios. Then my first real world assignment came when I was sent into Pontiac Studio. That would have been in December of ’59 or January of ’60—oh man, I’ll have to check my records! In any case, I was a junior designer in Pontiac Studio during 1960 and 1961.

It was my first production car studio and I was pretty fresh, pretty green. There was just one Pontiac production studio in those days. That was before the production studios were divided into multiple smaller studios. Jack Humbert was the chief designer and I was tremendously impressed with him right away. Jack became one of my heroes because he was such a fine designer. He earned my respect. His great strength, what made him stand apart from other designers, was his ability to finish a design; he had this precision, this eye that was absolutely dead-on. He could spot a bump in a line that was maybe a millimeter high; the guy had an awesome eye for refinement and adjustment of proportions and that kind of thing. In some cases, Jack could take a not particularly outstanding design concept and execute it with such exquisite refinement and taste that it came out looking wonderful. He had that touch. I learned a lot from him.

Q: Did he do the 1961 Tempest?

I believe he did although the ’61 Tempest and the ’61 full size cars were done before I got there. When I first went in to Pontiac Studio, Jack was putting the final trim touches on the ’61s. The ’62s were just being started. So whatever input I had as a junior designer was on the 1962s, both the Tempest and the full-size cars, and the new full-size body shell for ’63. Alas, after a year and a half or so, I was transferred out of Pontiac Studio. I think I may have been promoted to senior designer during my first stay in Pontiac.

Incidentally, Pontiac’s General Manager at that time was “Bunkie” Knudsen. My first encounter with him occurred when I’d only been in the studio for a couple of days. I came back from lunch one day a little early and I noticed this older gentleman wearing a dark blue suit sitting at my table and going through all my stuff. And I thought, “Oh my god. The end is near! I’m being fired. I did something wrong.” In those days, the hiring and firing procedures could be quite abrupt. If even the slightest thing went wrong, wham, you’re out. So I went in the back room immediately where we kept all the modeling supplies and I asked one of the modelers who was there, “Hey, who is that guy going through my stuff?” And he said, “That’s Mr. Knudsen. He’s the Pontiac General Manager.” Turns out he liked to look at the designers’ sketches. I left him strictly alone and let him look at all he wanted. That was that. Knudsen started a tradition at Pontiac of the General Managers taking an intense interest in the product. Pete Estes and John DeLorean, who followed in his footsteps, had the same turn of mind. They were truly product-oriented people. And product is everything.

Q: Did you have anything to do with the 1964 GTO?

No. I was out of Pontiac Studio when the ’64s were done. The cars I worked on as a designer on the board began with the 1962s. Jack assigned me to the ’62s and I dug into that. I did sketches for all the 1962 cars, a lot of sketches! I think one of my grille ideas, where the horizontal grille bars come across and then bend forward onto the nose, got on the final production ’62s. But there were three or four other designers in the studio with me and they were all trying to come up with ideas too. So the cars were really done, in the sense of being directed, controlled and finished, by Jack. I was just a part of the team. I did have some input into the “coke bottle” effect seen in the ’63 B-body (big cars) side shape. And I did the sketch that established the ’63 rear end theme where the bumper line at the corners folds up and over and then goes forward and down into the deck, forming those little winglets. That was from a sketch of mine that Jack liked. But then at the early stages of work on the ’63s, I was transferred out and I spent a couple of years in Advanced Studios doing other kinds of things.

And then, in the later ’60s, late 1967 or early 1968, I was transferred back into Pontiac as studio chief. Jack was bumped upstairs. He became the executive designer in charge of Chevrolet and Pontiac. He still spent a good deal of time in Pontiac Studio—it was kind of his old stomping ground. We all thought so much of Jack. It was family-like, even while I was studio chief. It was during those years I worked on the GTOs, and LeMans, Catalina, Bonneville, etc. I had the whole spectrum of Pontiacs. That was before they broke up the single studio that had existed into two studios Pontiac 1 and Pontiac 2. I kept Pontiac 1 studio and Ron Hill took over Pontiac 2. This happened about the time the ’73 were being finished. I started the front end on the ’74 Firebird, for instance, but Ronnie finished it.

Q: Did you work on the ’68 GTO and did you design the Endura nose?

I did work on the ’68 but I didn’t do the Endura nose. Actually, in 1965 and 1966, while I was in charge of a studio called Advanced 2, I did what became the 1968 GTO theme. I had what I thought was an interesting body theme idea and asked one of my guys, a very talented designer named Alan Flowers, to do a full-size tape of it for me. It went over well so we modeled it full size. The first try was pretty crude, but eventually we got those side blisters to stretch and put the way we wanted. Weeks later, when our advanced studio phase of the work was done and the basic form of the car was there, it went up stairs to Jack Humbert. Jack and his group finished the car. The front end that I had on it when it went up was actually the weakest part. Fortunately for everybody and certainly for the car, Jack came up with a better front end. I don’t know who in Jack’s studio actually came up with it. I’ve been trying to find out off and on for the last couple of years, though. The Endura concept, I think, did come out of Pontiac Engineering. But I’ m not absolutely sure. Herb Kadau, our liaison man with Pontiac might know.

There was a young designer who was in Pontiac Studio during those years named Brian Wuerker. He was very bright, very gifted. He might have done it. But that front end is absolutIy important. It was a wonderful breakthrough. It set a trend we see today in the bumperless look that almost all new cars feature. It really completed it. I wish I could tell you I did it, but I can’t. But I felt terrific about it.

The actual back end I had on the car when it left my Advanced Studio wound up being the ’69 production back end rather than the ’68. For ’68, Jack mounted the tail lamp in the bumper. Putting lamps in the bumper was a big thing for a year or two. For ’69 he took them out and put them back up in the deck like we had them on the Advanced Studio model when it went up stairs. Summing up, it was the basic body theme, the monocoque shell form with elliptical pressure bulges over the wheels—my contribution to the ’68 GTO.

Q: Let’s discuss the ’70–73 F-cars…

By the time I got up to being Studio Chief, the ’69 was in it final phase. Wayne Viera, my assistant, was leaning up the detail work on that car—the scoops and blisters and some of the Trans Am stuff. But basically that car was done. Oh yes, Wayne also did some refinement around the Lexan panel surrounding the headlamps . I didn’t identify with that car personally. But that ’70-1/2 second generation Firebird was another story altogether. I was absolutely crazy about that car from day one and really threw myself into it. I put the best designers I had on it and we were on consciously trying to create an important American sports car. We knew we had our chance and we wanted to do it bad!

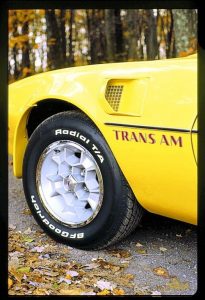

Q: Tell us about your role in creating the Honeycomb rim.

That wheel was my brainchild. I have the design patent on it, shared with Maurice (Bud) Chandler, one of those talented designers I mentioned. I asked Bud to watch over the wheel through the clay and plaster stages, until it left Design Staff. Many years later, Bud came up with the theme of the so-called “tube car” that evolved into the ’95 Oldsmobile Aurora.

But back to the honeycomb wheel. It was inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes that I had admired since I was a student. The idea of doing a wheel with a deep cell structure that would be inherently strong, not only radially but laterally, was intriguing. My intent was that it be an alloy wheel but that idea never made it into production. Somewhere in Pontiac Engineering the Polycast idea got attached to this design, much to my regret. In the Polycast approach, all of the structural requirements are taken care of by the underlying stamped steel wheel. The honeycomb pattern (now an injection molded appliqué) merely goes along for the ride, reduced to just so much pastry icing, only there for its decorative pattern. Its potential for structural integrity is lost which is too bad because, as things ended up, the Polycast wheels soft and more easily damaged. It doesn’t look as finished as it ought to and is too heavy.

In my opinion, it was an unsatisfying. To this day, I wish I could see our original design done in aluminum.

Q: What’s your favorite Pontiac?

Easiest question so far. It’s the Second Generation ’70-1/2–’73 Firebird. I guess of the several versions, probably the ’72 has the edge because I like the grille—a horizontally stretched honeycomb. I did that to with the honeycomb wheel. The grille and the wheels tied it all together. I like them all.

I always kind of wished the double-scooped hood that became the Formula hood, originally done for the Trans Am, would have prevailed because it’s functionally superior. Those twin boundary layer scoops up front really gulp in the air! But a lot happened. California emissions laws started getting really ferocious and even noise—they were testing for noise at that time—became an issue and so the whole ram air thing kind of got cut off at the knees. Of course, the Trans Am’s shaker scoop is entertaining beyond belief, even if it is less efficient from a functional standpoint. It’s too far forward to catch the high pressure area at the base of the windshield. Those frontal scoops just work better. It’s a personal thing of mine.

One of the design approaches pioneered in the ’70-1/2 F-car and that’s coming into the industry in a more wide spread way now, is the integration of the interior and the exterior. John Shettler was in charge of the interior. He became Pontiac Interior Chief. Johnny and I had areal empathy for forms and shapes, a lot of the same philosophy. As we were developing the exterior of the car, I actually had templates taken off the grille openings and the nose profile. John used those for the seatback shapes, the instrument panel cowl shapes, and so on, so that the exact same curves were used through the interior and exterior of the car. When you open the door of the Firebird, there is—I would like to think—a subliminal sense of the unity of the interior and exterior. That had never been done before, that I know of. Shettler was an insightful guy who sensed the importance of the interior and the exterior being two aspects of the same shell. He perceived that and he acted on it.

I remember John (DeLorean), on more than one occasion during his reviews, coming in to the interior studio and sitting in the interior model seating buck, moving his hand off the wheel and down onto the shift lever. And if it wasn’t quite right—like if your hand didn’t exactly fall right where it should have when you reached for the shifter, or maybe for a switch—he and Johnny would talk about it, make modifications and try again. There was a sense of the total car, being in it, and having things fall to hand, located in the right places. Everyone involved with that vehicle wanted it to be really good, not only from a performance standpoint but from an ergonomic standpoint.

John Shettler and I had a major stake in the aesthetics of the car and they dovetailed nicely with those driver-oriented ideas. It was one of the few cars for which I felt the entire team was in sync. Everyone knew we wanted all components to work—so, for the most part, no one went off unilaterally and did his own thing.

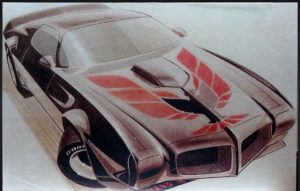

Q: Tell us about the Trans Am’s “screaming chicken.”

I did the original big hood bird (for the 1970-1/2 Trans Am) and Bill Mitchell rejected it. A designer named Norm Inouye in our graphics department worked it out, based on a sketch I did on a napkin one day. I saw Norm in the cafeteria and suggested, “Hey, Norm, how about doing a big huge bird for us, something like this?” He developed it and played around with the feather shapes and so on. Originally, the big bird was a little more bristly, less fluid than what became the actual production hood decal. Pontiac wanted a couple of Firebird show cars, one blue and one white, for the airport circuit and Herb Kadau sent them down so I could layout the birds and have them painted in our shop. Actually, this original big bird was even bigger than the ’73 production version, if you can believe that. I taped the bird on the white car first and Mitchell saw it in the paint shop and just went into one of his horrible tantrums. I was back in the studio. He called me up and I had to hold the phone away from my ear. That was the end of that! Then, a couple of years later, John Schinella talked him into taking another look at it. I don’t know how John did it —maybe the times had changed. John had a way with Mitchell that I never did. And so it finally saw the light of day on the ’73 cars. Mitchell was a real hair-trigger.

Q: What’s your view of Pontiac today? Has corporatization negatively affected Pontiac’s identity?

Certainly not, so far as appearance is concerned. I think the Pontiacs on the road today are still quite distinctive. I feel like the Pontiac design team is one of the strongest groups in GM design today. It’s got some of the most talented people. There’s a sense of mission and unified purpose about them. Even though I’ve been with Buick since 1980, I’ve always had a special liking for Pontiacs. I’ve had occasional contact with Pontiac folks over the years. Before I retired, I worked shoulder to shoulder with Pontiac designers because the 2000 LeSabre, which I was finishing up at the time, and the Pontiac Bonneville were being completed in the same big body studio. The Pontiac designers understand the mystique-they’re totally steeped in it. They are a strong group of designers who have a feeling for the product and commitment to its character. At least they did when I retired in 1996. Staff reorganizations can shuffle the deck, of course, but given the group that I knew in ’96 and given their orientation, I think Pontiac’s future from a styling and design standpoint, will continue to track its own distinctive course.

Addendum 2019: As a kid, I grew up practically worshipping guys like Porter, DeLorean, Mitchell and the other members of the automotive pantheon. But unlike most, I got to meet Bill, in person and one-on-one. Which is like a Star Trek fan getting a chance to have a beer with Shatner – only better, because Pontiac was real and Porter was there when GM’s performance division was at is apogee. He was one of the men responsible for some all-time greats, the kinds of cars they just don’t make anymore – because they can’t make them like that anymore.

I’m grateful I got a window into how it was – and will never be again.

. . .

Got a question about cars, Libertarian politics – or anything else? Click on the “ask Eric” link and send ’em in!

If you like what you’ve found here please consider supporting EPautos.

We depend on you to keep the wheels turning!

Our donate button is here.

If you prefer not to use PayPal, our mailing address is:

EPautos

721 Hummingbird Lane SE

Copper Hill, VA 24079

PS: Get an EPautos magnet (pictured below) in return for a $20 or more one-time donation or a $10 or more monthly recurring donation. (Please be sure to tell us you want a sticker – and also, provide an address, so we know where to mail the thing!)

My latest eBook is also available for your favorite price – free! Click here. If that fails, email me and I will send you a copy directly!

Thank you. Excellent read.

Hi Jet,

My pleasure; thanks for the kind words!

Here you go. 1973 Firebird Ad.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2xXvsPlRis

Given all the rot around us, I’d almost rather have not known how it was. Greta Thuneberg wails about her dreams being taken from her. How about ours? The disintegration is real and happening and there’s not a damned thing that a small unorganized group like us can do about it. Not a thing

This disintegration of talent is happening through all industries today. Especially in the chemical industry. Too many codes of conduct and slavish adherence to “government regulations” is killing any original ideas.

Government has a dulling effect on that kind of stuff…

Great stuff. Thanks Eric.

Brings back a lot of old memories as I really wanted to be a car engineer. Even visited GMI in Flint at 18 yrs old. Was hard to come up with the plane flight cost, and I remember getting run around by the taxi guy but I was to naive/scared to say anything. But it was apparent to me even back in the late 80’s that it wasn’t the college or environment for me and I went another direction.

How awesome would it have been if Pontiac made a tribute car like the early Firebird instead of the Holden/GTO. It certainly worked for the Challenger.

Great interview and you asked questions he wanted to answer, apparently, which is good. Car guys designing cars for people, not for mandates. The evil of that free association and free market ideology! (think of the children/safety)