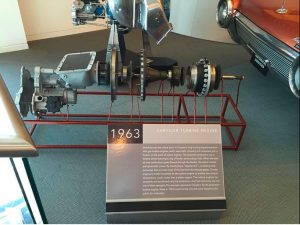

The failure of Chrysler’s turbine cars – back in the ‘60s – gives us a parallel, historical case study about why electric cars have failed today.

And yes, they have failed.

Else it would not be necessary to force car companies to build them – nor to pay off people to “buy” them. The fact that both things are absolutely necessary is damning evidence that electric cars are the rolling dead – so to speak. Or would be, if the things which drive their inanimate lives (the bayonet and the sawbuck) were to be withdrawn.

Chrysler’s turbine cars had their merits – just as electric cars have theirs. And the chief merits of the turbine cars were actually very similar to those of electric cars.

First, they were much simpler and so lower-maintenance than piston-engined cars.

A turbine – like an electric car’s motor/battery pack – has fewer moving parts. It does not need peripheral systems, such as a cooling system filled with antifreeze.

There is no radiator, hoses, thermostat, fan or water pump.

A turbine doesn’t need its valves periodically adjusted, its points set or its oil changed.

Chrysler’ turbine has just one spark plug.

A turbine engine produces almost-instant heat for the car’s passengers, a boon in winter and just like an electric car – which generates heat not by combustion but by electrical resistance (heating a wire/coil) and passing air over the heated surface, via a fan, into the car’s interior. This is much faster than waiting for the engine in an IC-powered car to heat the coolant and then transfer some of that heat to the car’s interior.

The turbine-powered had other virtues, too.

It started easily in extremely cold weather (Chrysler tested them down to minus 20 degrees) something which most of the cars of that era had big problems with.

And a turbine can use almost any liquid hydrocarbon fuel – gasoline, diesel, kerosene. Even Chanel Number 5 perfume – and that’s no joke; Chrysler actually demonstrated this in Paris.

They were the first “flex-fuel” cars.

Turbines are also exceptionally smooth, almost entirely free of vibration – another thing in common with electric cars.

Plus, they were “futuristic,” different.

But the turbine-powered cars’ advantages and general coolness were not enough to outweigh its several disadvantages.

They didn’t melt the asphalt or peel the paint off the panels of any car within range of the turbine-powered car’s exhaust – as some fables have it. In fact, Chrysler went to great lengths to cool the exhaust of the turbine-powered cars (using heat exchangers) to a temperature of around 140 degrees – much cooler than the exhaust of a piston-engined car.

And they proved to be as everyday drivable as any other car – more so, in some ways.

Chrysler actually put 50 of them into circulation – in the hands of ordinary people, who signed up to participate in a pilot “public user” program.

The cars didn’t reveal any significant operational problems – unlike electric cars, which do have them.

The problem that slew the turbine car was its value proposition.

They were wallet-curdlingly expensive – just like electric cars are, today. Chrysler estimated the cost per car at about $20,000 in 1963 dollars.

That’s about $165,000 in today’s money.

Meanwhile, you could buy a brand-new 1963 Polara sedan for about $2,500 – just over $20,000 in today’s money.

And the turbine car’s mileage (whether running Kerosene or gas or Chanel Number 5) was about the same (mid teens) as that delivered by an otherwise comparable car of the period, which was a function of the turbine “idling” at 20,000 RPM.

So there was no economy advantage to be gained – and the operational advantages (including the convenience of being “flex fuel”) weren’t enough to over-ride the disadvantages of the wallet-curdling cost.

Which reduced the appeal of the turbine-powered cars to that of being different.

Just like the appeal – such as it is – of today’s electric cars.

They cannot tout an economy advantage, because they cost so much more (even with heavy subsidies) than otherwise comparable cars.

Electricity may cost less than gasoline, but if the car costs 30-40 percent more than an otherwise comparable non-electric car, that becomes as irrelevant, in terms of economic considerations, as the value of sunscreen cream to a spelunker.

They cannot tout superior range.

And while it’s nice to be able to charge up at home, it’s not-so-nice if you haven’t got time to wait for the car to recharge. These disadvantages outweigh the advantages, at least for most people – or rather, for enough people. The critical mass necessary to make the difference between success and failure.

Which brings us full circle to the difference between 1963 and today:

Chrysler’s turbine cars had to sink – or swim – on the merits. Of which there were more than today’s EVs.

Functionally, at least. There was the Flex fuel thing, of course. Handy.

And it didn’t take forever to recharge. Its range was about the same as that of any other car, too. But it wasn’t enough – because the car cost too much and didn’t save the owner enough. Different only takes you do far.

There were no mandates, no subsidies back in 1963, so the turbine cars had to be better (more efficient, more economical, etc.) than the cars they hoped to replace.

They weren’t – and so became museum pieces. An interesting idea – but not a better one.

EVs aren’t better. In many ways, they are worse.

But they survive – thrive – because of mandates and subsidies.

They float on the backs of those who don’t want them, but who are forced to pay for them – for the sake of those who do want them, but aren’t willing to pay full price.

They are a step backward – nudged forward by the bayonet and propped up by someone else’s sawbuck.

. . .

Got a question about cars – or anything else? Click on the “ask Eric” link and send ’em in!

If you like what you’ve found here please consider supporting EPautos.

We depend on you to keep the wheels turning!

Our donate button is here.

If you prefer not to use PayPal, our mailing address is:

EPautos

721 Hummingbird Lane SE

Copper Hill, VA 24079

PS: Get an EPautos magnet (pictured below) in return for a $20 or more one-time donation or a $5 or more monthly recurring donation. (Please be sure to tell us you want a sticker – and also, provide an address, so we know where to mail the thing!)

My latest eBook is also available for your favorite price – free! Click here.

Americans used to believe in freedom.

http://www.campidiot.com/ci/viewforum.php?id=28

Eric,

It looks like in Italy they will start taxing “larger” cars to finance a subsidy for electric cars.

If you don’t mind, I’d like to translate this article in Italian and post in on my blog:

http://planetoplano.blogspot.com/2013/03/elon-musk-mi-ispira-una-simpatia.html

Thanks,

Leon.

Hi Leonard,

I’m not surprised – and thanks for the word about this vile business! Also, herewith my blanket permission to translate/reprint any of my stuff!

Thank you.

Italian version:

http://planetoplano.blogspot.com/2018/12/il-bastone-e-la-carota-sono-i-due.html

Best,

Leon.

The turbine concept was studied starting in March 1954 into the early 80’s & there were 6 generations of turbine engines. Emissions were always a critical design parameter.

Per Chrysler’s internal book on the” History of the Chrysler Corporation Gas Turbine Engine Vehicle” published by the Engineering office of Chrysler in 1974: Chrysler submitted a 1973 Dodge coronet 4 door to the EPA for evaluation as part of winning the 3.5 million dollar contract that called for the development of a turbine powered automobile which met 1977 emissions requirements and had comparable fuel economy to piston engines with a mass produced power plant at comparable costs.

The 50 car public eval program used the 4th gen engine. A traveling exhibit began visiting shopping centers across the USA in Jan 1964. From Sept 12, 1963 thru Jan 8, 1954 the cars were shown in 23 cities in 21 countries. It was one of the most popular attractions at the 1964-65 worlds fair. One was used for display and one for rides. Several were used on a tour of colleges.

Gen 6 weighed 600lbs. 150 bhp with 470 lb-ft of torque and ran on unleaded, diesel, kerosene, JP4 etc.

You owe me a clover sticker

Those were enormous torque figures for the time in relation to horsepower. Like greater than 3 to 1.

IF the turbine engines could indeed be produced with no greater a cost premium than, say, a diesel engine with comparable numbers for torque and horsepower, and a reasonable life-cycle, then they might indeed have caught on. The multi-fuel capability was a big plus.

Of course, a decent automotive turbine would have been a tremendous boon to the military, particularly the Army and the USMC with their need for not only tanks, IFVs, SPGs, and similar armored combat vehicles, but also gi-normous fleets of trucks and specialty vehicles. However, with the notable exception of the M1 Abrams family of MBTs, gas turbines haven’t found use, not only due to cost concerns but mainly very poor fuel economy. A jet engine works great since most jet aircraft operate at constant speed and nearly flat-out; therefore, their operation can be optimized with regard to fuel consumption. This is usually impossible with most land vehicles, particularly those employed for military use.

The Honeywell AGT-1500 used in the Abrams tank does indeed propel that 70-ton beast at a rapid pace; but it’s fuel consumption is about TWICE a comparably-powered tank diesel (like the MTU803 used in the German Leopard II series). It wasn’t considered too great a handicap since the original role of the Abrams was to fight essentially a defensive battle against a Soviet-Bloc invasion of Western Europe; that is, if “Ivan” came crashing through the Fulda Gap and across the Northern German plain, with more tanks than “Gawd”, the Abrams would operate close to its supply and, in a pinch, be able to fuel up from civilian sources of diesel, unleaded gas, or heating oil. Of course, “Ivan” stayed put on his side of the “Iron Curtain”, and the Abrams saw service in both Desert Storm in 1991 and Iraqi “Freedom” in 2003. In both operations, the M1’s thirst proved a significant logistical constraint, leading to such hilarious improvisations such as dropping in some Rangers and Engineers well behind enemy lines in the expected advance route of the tanks, digging a fire base, then having the Chinooks and SkyCrane bring in JP-4 in bladder bags to wait for the tanks to fill up! Serious consideration has been given to ditching the gas turbine altogether and building the German engine under license for the M1A7 upgrade, even though plenty of surplus AGT-1500 turbine engines are available due to downsizing of both Army and USMC tank parks. The Russians had designed and built the T-80, a development of their ill-fated T-64 (their first “high-tech” tank which was a persistent “problem child”) with its gas trubine engine. Like the Abrams, its high fuel consumption was problematic, as well as the hot exhaust kept accompanying infantry from riding on the tank’s rear deck (the time-honored Russian practice of “desanti”) and made it every more vulnerable to heat-seeking missiles, which Chechnyan rebels in 1995 and 1998 somehow obtained and used with devastating effect! The Russian Army promptly retired its surviving T-80s without further ado, deeming it unsuitable for combat!

I think this summarizes well the reason some would buy a tesla “Owning a Tesla is a bit like being an Apple user – deep down you know you have paid far more for an inferior product, but it has the street cred so you may as well surf that hype curve for as long as you can.”

https://www.quora.com/Why-did-you-sell-your-Tesla/answer/Alan-Williamson-31?ch=2&share=6a44e19a&srid=2eDN

Hi A,

Yes – with a key difference. Apple isn’t mandated or subsidized. Tesla (and EVs in general) are. People (me among them) freely pay more for an Apple product, for a variety of reasons (I like that Macs are much more stable and much easier to use than a PC) and they pay full price. They don’t leverage the government to force other people to “help” them buy their Macs and iPads.

Apple used to make a superior machine. I’ve opened up many an old Mac (1990s) and they were well put together, thought out, nice inside. SCSI hard drives too. Then from the late 1990s the decline began to where they are today.

Same reason folks buy those stupid Priuses (or is that Prii?)…you can virtue-signal as you drive!

Chrysler’s Turbine car did not need a torque convertor, as the output shaft of the engine was not mechanically coupled to the power-producing section of the engine.

The major downside to the Chrysler Turbine car was fuel availability. Leaded gasoline could not be used. Unleaded gasoline was not available at the time, and kerosene and diesel fuel were not as available in those times.

Throttle response was also somewhat problematic, as it takes time for a turbine engine to “spool up”, its performance being similar to a “bog” in a carburetor-equipped vehicle.

That being said, if anyone could develop an automotive turbine engine, Chrysler was it…

Lead-free gas certainly was available at the time, but was not common as only one major oil company was selling it before unleaded gas was mandated in the 1970s.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amoco#Lead-free_gasoline

In the 1960s “lead-free” gasoline was known as “white gas” and was available in very limited and small quantities, such as would have been used in lanterns and other small appliances. “White gas” was difficult to find, hence, the Chrysler turbine car was limited in fuel availability.

It was limited in the sense that it was not pervasive as it is today, but unleaded gas was available anywhere Amoco gasoline stations were found. Amoco stations were pretty common in my area. (I’m sure this varied in different regions of the country.)

Amoco even advertised the virtues of their lead-free gas:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGqOhUDsuo8

Given time I think they might have had more of a chance. After all the history of the turbine started with the RAF experimenting with turbochargers on rotary piston aircraft. Even though the reasons for turbocharging are dubious, with the volume of turbo’d cars increasing and access to tooling that can build to the tolerances needed they might become viable.

I would think a turbine driven hybrid would be a fantastic drivetrain. Let the turbine do what it does best, run at a constant RPM, turning a generator for cruise and recharging super capacitors or a small lithium iron phosphate battery bank for jumping off the line. Downside is that you have yet another piece of equipment to deal with, since most hybrids use the motor as generator. And not so sure of the differences in efficiency of power cables vs driveshafts. And adding electric traction motors might end up weighing as much as a transmission too, unless you really undersize them and put one per wheel. But there goes the complexity again…

If you haven’t seen it, you need to watch the episode of Jay Leno’s Garage where he takes his out for a spin:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b2A5ijU3Ivs

Oh poop, you beat me to the punch posting the link to Leno’s Turbine car, lol. If you watch the video, he has a 1975 Honda CB400F parked behind the Turbine Car. I restored one of those myself, but like an idiot, I sold it to some dipshit that has no appreciation for what it is, and it still had the original 4-1 exhaust which it very sought after! I kick myself for every landmark vehicle I had to sell just to make space or pay bills! I’m going to bed and cry now.

Theres also the Ford Nucleon of course https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ford_Nucleon

I dont think they were that fast actually. Kudos to Chrysler for trying it but a small jet engine in a car isnat actually a good idea I guess ha.

Hi Mark,

They weren’t fast; Chrysler designed them to be about as quick as other sedans of the era. The problem – as today – was that car cost too much and didn’t save you enough.

I’d rather see 3 million Chrysler Turbine cars farting around the country than a dozen phoney govt-subsidized shitboxes that will be the inevitable result of all this political meddling.

Eric,

I had forgotten all about turbine cars until you mentioned it here. Great body design.

Trying to remember….how did they compare in power, acceleration, and mpg to the piston engine cars of that era? Obviously academic, at that huge price disadvantage. But I’m still curious. Thanks!