If you’ve ever hunted deer, you know that a dead deer can run for a surprising distance before it realizes it’s dead.

So it was with Studebaker, one of America’s most famous deceased car companies. Though doomed by competition it could no longer compete with – the company wasn’t making enough money selling cars to have money to design and manufacture new cars – it had one last leap left in it.

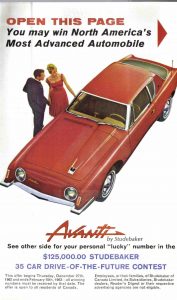

This was the Avanti – the final Studebaker.

It is a car many people still know about today, even people who couldn’t tell you anything about Studebaker. Probably in part because of its arrestingly original appearance but also because even after Studebaker went for a sleep with the fishes in 1966 (two years after the last Studebaker-built car rolled off the line) the Avanti resurrected itself a number of times, as various interested parties acquired the right to the name and the tooling needed to build more of them.

But the last one made by Studebaker was back in ’63 (for the ’64 model year) a mere one year after the car was first brought out as the last-best hope for Studebaker.

It’s a shame that Studebaker didn’t make it sooner . . .

By the time it did, it was already too late.

In the early ‘60s, the South Bend, Indiana-based automaker was rapidly running out of money, despite a merger with Packard (also Doomed) in 1956 that was supposed to have pumped up the bottom line by merging the means of two companies into one.

But Packard – by 1956 – was about as healthy as Colin Powell in 2021.

Though favored By Stalin, after the war, Americans had lost interest in Packards – which had once ranked with and even ahead of Cadillacs and Lincolns . . . before the war. Probably because after the war, Cadillac and Lincoln began outfitting their cars with modern overhead valve V8s while post-war Packards were still powered by increasingly obsolete flathead in-line sixes and eights that dated to the pre-war era. These were installed in controversial body shapes that one automotive writer – the legendary Tom McCahilll of Modern Mechanix – dubbed as having the appearance of “a dowager in a Queen Mary Hat.”

Attempts were made to make post-war Packards more appealing to other-than-dowagers, including the ’53 Caribbean convertible – which was supposed to sway potential buyers away from Cadillacs and Lincolns.

But it was like using a squeegee on the Titanic’s windshield to prevent her from sinking.

Nothing could stop the deluge – or rather, the hemorrhage. GM and Ford sensed Packard’s weakness and made for the kill by under-pricing their popular models, management knowing they could afford to eat the loss – but Packard (and Studebaker) could not.

The merger did result, temporarily, in America’s fourth-largest car company – the Studebaker-Packard Corporation. But the underlying problems weren’t resolved; rather they were concentrated. For a few years, Studebakers were sold as Packards – or rather, an attempt was made to sell them that way. Not many bought them. Also, Packard’s number-crunchers had apparently not been fully aware of just how broke Studebaker was until after the merger, when it was too late to erase the signatures on the contracts.

But Packard would not go down alone.

Packard ceased even trying to sell cars after 1958, leaving that to the Studebaker remainder of the partnership. There were some interesting models, such as the Lark series, which were among the first cars American of the era designed to appeal to the emerging youth market and as alternatives to small, economy-minded cars from European manufacturers.

The cars were offered in two and four-door versions as well as a two-and-four-door wagon iterations. A convertible was added to the mix in 1960 (1959 being the first year for the Lark series). Despite offering a modern V8 engine as an option and features such as a folding cloth “Skytop” roof, these Studebakers weren’t able to make much headway against the offerings of GM, Ford, Chrysler and even the Nash-Hudson combo that became AMC (not yet terminal; the death of AMC being still decades in the future).

Apparently, economy wasn’t doing the trick.

Maybe something beautiful would

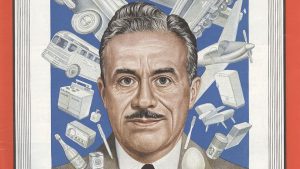

Raymond Loewy was just the man to conjure it up.

He had been doing so for the past 30 years-plus.

Technically he was an industrial designer. But his work was art. Many today do not register his name. But everyone knows what a Coca-Cola bottle looks like. Loewy designed that. Also the blue over white with gold trim and black lettering color scheme applied to Air Force One, which he did at the request of Jacqueline Kennedy for JFK’s Boeing 707.

Prior to that, he penned the iconic look of the Streamliner (GGI) class of high-speed electric locomotives operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad, beginning in 1934.

These showcased a number of innovations – including a frame that could bend slightly at a center joint (using a ball and socket to connect the two halves) which allowed for higher speed around curves. But it was their rifle-bullet looks that made them industrial-era icons.

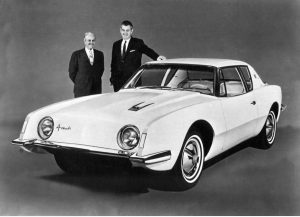

Perhaps such a man could get Studebaker back on track. The president of the company, Sherwood Egbert, approached Loewy to see whether he might be willing to give it a try. What he came up with – in just six week’s time – was what ultimately became the 1963 Avanti, the last and arguably best car Studebaker ever produced.

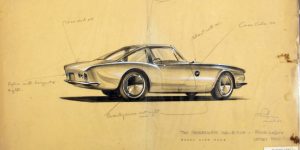

It was without question one of the most distinctive-looking cars ever made, especially up to then. It was ultra-modern and sleek, characteristic of Loewy’s designs. The car was almost entirely free of the over-styled chromed embellishments that were typical of Americans cars of the period, It was streamlined, like JFK’s 707. There was no grill – perhaps the most striking thing about the car’s appearance. Cooling air for the engine was drawn from underneath the slim-line bumper that protected the twin pontoons of each front fender, with the headlights set flush in a body-colored panel that greatly enhanced the Avanti’s aerodynamics as well as completely set it apart visually from any other car on the road.

Viewed from the side, the car seemed poised to launch, with the rear suggestively higher than the front, like a cat getting ready to end an unsuspecting bird.

From behind the wheel, the road ahead was targeted by a raised “gunsight” that tapered from the cowl area to the forward part of the hood, where a stylized Studebaker lightning bolt emblem was affixed.

Loewy described this as designed to point “where the roadway would bend with the horizon.” The long hood was offset by a shortened trunk, which the passenger compartment seemed to flow toward over a large and very complex convex rear glass that provided a panorama view of what you’d just left behind.

Which was pretty much every car on the road back in ’63.

Three engines were available, beginning with a 289 cubic inch V8 advertising 240 horsepower. This was not a Ford 289 V8 engine. It was an entirely different engine, designed and built by Studebaker rather than bought from Ford and installed – as a number of people mistakenly assume. The R1 289 that became the Avanti’s standard engine was the latest iteration of Studebaker’s first post-war, overhead valve V8, which emulated the design of Cadillac’s first (1949) post-war OHV V8, the 331.These two engines are so close – in some ways – that a Cadillac intake will bolt directly to a Studebaker V8, although the ports won’t line up without some hogging out.

No parts except a few bolts interchange with a Ford small block V8.

It was not a large displacement V8 – as the Cadillac V8 eventually became. Its capacity was limited by piston design, which did not emulate the Cadillac’s “slipper” pistons. The Studebaker V8’s stroke was thus limited, hence its displacement – which was initially 232 cubic inches.

But it was a strong engine, with a big, heavy cast iron block that could safely handle high horsepower. Bearing surfaces were large – especially for its size – and there were a number of unique design elements not shared with Cadillac’s V8, including a gear-driven camshaft. GM – and Ford’s – V8s as well as almost every other V8 used a timing chain, which would inevitably stretch over time, causing timing problems. Also unlike almost post-war V8s, the Studebaker V8 used mechanical rather than hydraulic lifters to open and close the valves. The latter offered the benefit of quieter running and zero maintenance – but the former allowed for higher RPM operation, because solid lifters don’t “float” at high RPM – which is why many of the highest-performance V8s offered by GM and Ford and others in the ‘60s also used solid lifters.

The 232 Studebaker V8 summoned 120 horses – which was competitive with the power produced by other early post-war OHV V8s, such as those offered by Cadillac and Oldsmobile (RIP). By 1955, the Commander V8 – as it was marketed by Studebaker – was making 162 horses – and up to 259 cubic inches. Better breathing – via larger intake and exhaust ports – were chiefly responsible for the power gains.

Even more power was gained when Studebaker decided to offer a factory supercharger option – available initially with the Golden Hawk of the late ‘50s. This “Sweepstakes” engine – now up to 289 cubic inches – developed 275 horses.

Engine – and car – would merge in 1963.

The R1 289 – and 240 horsepower – was just for openers. The R2 supercharged version belted (literally, the Paxton supercharger was mechanically driven by an accessory belt) out 290 horsepower. And if that wasn’t enough power, there was a third version – the R3. This was a very low production, also supercharged but custom-tweaked by Paxton’s Andy Granatelli who took an R3 Avanti up to 170-plus MPH on the Bonneville Salt Flats setting a new Class C production car speed record.

Avantis’ with the R1 engine weren’t quite that fast – top speed for them was just over 120 MPH. But they were pretty quick, capable of getting from zero to 60 in about nine seconds. This was excellent performance for the time but if more was desired, specificing the R2 engine knocked two full seconds off the 0-60 run,making a ’63 Avanti one of the quickest cars available that year.

But as good as it looked – and as fast as it ran – the ’63 Avanti was a bit too forward for Studebaker, at the time. While the fiberglass used for the car’s body allowed for shapes that would have been difficult to render in stamped steel, fiberglass is also notorious for fit and finish problems and these plagued the Avanti, delaying and limiting production of the car and causing bad feelings among people who bought the handful of cars that were trickling off the line.

The scheduled release date of 1962 – as a new-for-1963 model – ended up being almost 1963. Only about 1,200 cars were shipped during the 1962 calendar year – and just under 4,000 cars in total were made during the 1963 calendar year. This was nowhere near the production volume necessary to make rather than lose money on the car – and by 1963, losing more money was something Studebaker could no longer afford.

The smell of death was in the air by now – and despite the Avanti’s stunning styling, buyers were shying away from a company that everyone could see was teetering on the edge of the grave. Few people want to buy a car orphaned by the demise of its parent. Parts and service dry up. Warranties aren’t worth much when the company that issued them no longer exists.

Avanti sales declined by more than two thirds for what proved to be the final year – for the Studebaker Avanti. However – and fortunately, for those who admire the Avanti – the car survived Studebaker, which bequeathed life after death to its final model by selling the tooling for the Avanti as well as the rights to produce it to Nathan Altman and Leo Newman, two Studebaker dealers who wanted to keep the Avanti alive.

It became the Avanti II – and was sold as the sole model of the new Avanti Motor Corporation. Visually, it was almost the same car but was now mechanically very different. With Studebaker gone, there were no new 289 Studebaker V8s available. So the Avanti II’s got Chevy-made 327 V8s, making 300 horses. The Chevy V8 was taller than the Studebaker V8, so the Avanti II’s hood and fenders had to be adjusted upward to make it fit.

It still didn’t sell especially well – probably because the Avanti II cost almost 50 percent more than a Studebaker-made (and powered) Avanti. This recreated the money problems that felled Studebaker. But the allure of the car was strong enough to keep Altman and Newman hanging in there through the early ’80s – and sufficient enough to persuade investor Stephen Blake to attempt another infusion of enthusiasm.

And cash.

A significant restyle was performed that shaved off the external chromed bumpers of the original car in favor of the then-trending (and now common) integrated/body-colored front and rear bumper covers along with an attempt to build a national dealer network to get the cars to potential buyers.

But ongoing problems with quality control – arising from lack of adequate funds to correct them – finally did to the Avanti II what they had done to Studebaker all those years before. The Avanti Motor Corporation went belly up in 1986 – 20 years to the year after Studebaker went for a permanent sleep with the fishes.

It is perhaps the only case in the history of cars of a dying car company’s last car being its most memorable and – arguably – its best car.

. . .

Studebaker Avanti (and Avanti II) Trivia:

-

- The ’63-’64 Avanti offered three versions of the “Jet Thrust” 289 Studebaker V8 along with three different transmission options. There were two manual transmissions (a three and a four speed) as well as a three-speed automatic designed in-house by Studebaker. This transmission was set up for second-gear starts – for the sake of smoothness – unless the driver applied throttle pressure sufficient to force a downshift into first.

- Because its body was made entirely of fiberglass, the Avanti was a very light car for its size – and otherwise. Curb weight was just over 3,100 pounds. This was in keeping with Studebaker’s design philosophy and Raymond Loewy’s dictum that “weight is the enemy.”

- Studebaker marketed the ’63 Avanti as being “America’s only four-passenger high-performance personal car,” anticipating (and inspiring) the muscle car explosion that began in 1964 with the introduction by Pontiac of the Tempest GTO. Studebaker hoped that the Avanti’s back seats would serve as a sales advantage over the two-seater Chevy Corvette and Ford Thunderbird.

- Standard equipment included power Bendix disc brakes, pleated “deluxe” vinyl upholstery and aircraft-style toggle switches, along with rear seat belts and a center console up front. Air conditioning was an available option – but only with the R1 (non supercharged) engine.

- The R2’s Paxton supercharger developed about 4.5 pounds of boost, which was sent through a Carter AFB four barrel carburetor housed in a special enclosed chamber to prevent pressurized air from escaping. The engine received a heavy-duty cooling system, a larger harmonic balancer and was equipped with a dual-point distributor.

- Though the Avanti’s bodywork is unique, its underlying chassis and suspension were based on the Lark series and many parts interchange.

- Just before the lights went out for good, Studebaker had been developing an even higher-performance R4 variant of the 289 V8, which had its displacement bumped up to 304 cubic inches. However, none of these were event installed in a production car.

Excerpted from the forthcoming (soon!) book, Doomed.

. . . .

Got a question about cars, Libertarian politics – or anything else? Click on the “ask Eric” link and send ’em in! Or email me at [email protected] if the @!** “ask Eric” button doesn’t work!

If you like what you’ve found here please consider supporting EPautos.

We depend on you to keep the wheels turning!

Our donate button is here.

If you prefer not to use PayPal, our mailing address is:

EPautos

721 Hummingbird Lane SE

Copper Hill, VA 24079

PS: Get an EPautos magnet or sticker or coaster in return for a $20 or more one-time donation or a $10 or more monthly recurring donation. (Please be sure to tell us you want a magnet or sticker or coaster – and also, provide an address, so we know where to mail the thing!)

My eBook about car buying (new and used) is also available for your favorite price – free! Click here. If that fails, email me at [email protected] and I will send you a copy directly!

Onan,now Cummins Power Generation,was a subsidiary of Studebaker Packard.Saw several of these sets still in use in LA in the80’s and 90’s.

I remember seeing the Avanti II’s on display at the Chicago Auto Show when I was a kid in the 1980’s. It was of course way different from any of the 80’s cars too. My dad told me the story of it being the last Studebaker. Of course those Avanti’s were not Studebakers.

The interesting thing about Studebaker history, that it was the only major wagon, carriage and harness maker to manage to adapt and move to making cars and light trucks. It was founded in 1852 so it was already a half century old when GM and Ford were founded at the beginning of the 20th century. The big three where the upstarts and Studebaker was the established company.

But 50 years later it was so poorly managed it went out of business not too long after it’s 100th birthday. It’s just another example of why two (or more) failing companies shouldn’t be merged together.

I think most of the time, the failure of a company is because of the failure of it’s leadership, not its products or its employees.

My dad almost bought an Avanti when they first came out. It was the most futuristic, breathtaking and beautiful (to me) American car I’d ever seen, both inside and out.

On the test drive, with my parents, the salesman and I all aboard, we discovered the Avanti was moderately peppy…….but extremely lacking in interior room. That’s what killed the deal for my dad. Although too young to drive at that time, I was very disappointed.

It worked out OK though. Dad bought a 1st gen Buick Rivera for the family car. It was much roomier……and way faster.

Eric,

I enjoyed this read on the Avanti. If this is a sample of your book coming out, I’m in for buying a copy. I always admired the Avanti when ever I saw one.

I hope you do a chapter in *Doomed* on the Datsun Roadster (my baby in my garage I’ve owned since 79). The roadster died a fitting death (1970)…right before smog regulations would have caused autoimmune disease and lung cancer for cars. The car was discontinued at it’s best performance. Like a rock star dieing in a plane crash… it died at it’s zenith. I digress.

Yes, the old Packards were “staid”…but they were also BULLETPROOF. My Dad was given a ’38 Packard, his grandmother’s old car, when he went to Fresno State College in ’51. He soon got the bug for a newer car, and being 18 at the time, traded in the old beast on a ’49 Ford, yes, the one with the last of the Flatheads. Although that ’49 got him through college and Air Force ROTC, enough to date and marry my mother, he regrets giving up the Packard.

Part of what sank the merged Packard-Studebaker concern was also that one of the Studie makes was rebranded as the Packard “Clipper”. The motoring public saw through it and rejected it, even though today Clippers are sought after by collectors.

Also, in 1952, there was a BIGGER merger proposed, one of SIX lesser automakers, Hudson, Nash, Willys-Overland, Kaiser, Packard, and Hudson. Without doubt, as there were significant overlaps in product lines, some models and perhaps one or two of the makes would have to go, but such a conglomeration, like GM some 40 years prior, would have resulted in a car company bigger than Ford (which had slipped to #3 and was being rebuilt by the grandson of the founder, Henry Ford II) and just about as big as Chrysler. I can well image it’d have survived, and maybe around ’80 or so, would have bought out the foundering Chrysler Corp. One of those that more or less sabotaged the proposed merger was an up-and-coming star in the auto business, a Mormon by the name of George Romney, later President of AMC, Governor of Michigan, and father of Willard “Mitt” Romney.

Very interesting article, Eric! I was ignorant of almost everything in this article, including the fact that Loewy designed the Avanti- I had always thought it was some Dago design. Loewy is forever known to many NYC-ites as the designer of the recently retired R40 “slant” subway cars from the late 60’s.

R40 Slants: https://images.cf.nycsubway.org/images/icon/title_ny_r40.jpg

Can’t believe that the Avanti was resurrected several times….it was a fugly car that really had nothing to offer other than looks, if one happened to like such looks; and compared to the offerings of the other manufucturers of the time it seemed like a downgrade in almost every category, other than uniqueness. As a niche vehicle, sure; but as a mass-market offering to save a company? Well, I guess that’s illustrative of the kind of decisions that reduced Studebaker to defunctness!

Funny though- how it is so common for mergers to not address the underlying problems but rather exacerbate them, as you mentioned- We see the same thing happening today with Fiat, Chrysler, Pewjit (Peugeot) et all becoming Stellantis, and Renault, Nissan, and Mitsubishit forming an alliance. It’s kinda like three incompetent plumbers teaming up and somehow each expecting that the other incompetent will save them- being too stupid to realize that it might only have a shot at working if the other plumbers were competent…but if they were competent, they wouldn’t need to team-up with the incompetent! And thus Moe, Larry and Curly’s Plumbing is born…..

Right after the war, George Mason of Nash realized that the postwar seller’s market would not last and wanted to combine the major independents into a single company capable of taking on the Big 3 while they were still in good financial health. That would have been Nash, Hudson, Studebaker, and Packard. However the others were all still making good money and declined.

Then the seller’s market cooled and the 1953 sales war between Ford and Chevrolet left the independents bloody and battered. By 1954 Hudson was in very bad shape, particularly after blowing all their development capital on the ill-fated Jet. (AMC would do much the same around 20 years later with the Pacer.) The line of “Step-Down” Hudsons which seemed so advanced in 1948 were looking stodgy and due to their unit construction could not be extensively restyled inexpensively. Hudson had no choice but merger and combined with Nash to form AMC, but that combination was not nearly as healthy as the original plan would have been. Had it not been for the 1958 recession that pushed the market towards economy cars and AMC’s line of Ramblers the company might well have folded back then. (As it was AMC was one of the only companies whose sales increased that year and they actually passed Plymouth in sales a few years later.)

By 1954 Studebaker was in dire straits. Packard was still somewhat solvent but their market share was quickly eroding and the company was looking for a partner with a larger dealer network and potential for larger sales. However the deal was essentially done on a handshake and Studebaker’s books were not looked at in any detail. After the merger was complete was found that Studebaker was in much worse shape than anyone knew and instead of being an asset, Studebaker dragged Packard down with them.

The short-term success of the 1959 Lark infused Studebaker-Packard with cash that was used to diversify into a mini-conglomerate. The company did not actually go out of business, it simply closed the automobile division in 1966. The rest of the company later disappeared into multiple acquisitions over time.

Good stuff, Jason! I love Hudsons….and pre-Gremlin AMCs. The demise of the smaller manufacturers seems to have been more so suicide than sabotage. In their dying days they made fatal decisions which helped put them out of their misery. I wonder how much of their problems were caused by trying to compete with the biggies, rather than just being content to do what they do and enjoy the segment of the market that wanted an option that the big three didn’t offer? (Kinda like Ebay always wanting to compete with Amazon, and thereby destroying what made it great years ago- Now it’s just a second-rate over-priced China-mart more expensive Amazon).

I see that so much in business- from small one-person businesses to giant corps- They’ll sacrifice a good positions and alienate loyal customers for a shot at trying to take a part of someone else’s pie. It usually ends badly for all involved.

AMC’s success in the late 1950s and early 1960s was due to George Romney’s policy of finding niches that the Big 3 were not addressing, in particular compact cars. When Romney left for a career in politics Roy Abernethy took his place and took the company on a suicidal campaign to take on the Big 3 model-for-model.

He may not have had much of a choice though. Early on no one else was making compact or intermediate-sized cars, as they were then known. Then in 1960 the Big 3 entered the compact car fray, and by the mid-1960s they were fielding a range of intermediates. AMC had nowhere to hide unless maybe they had doubled down on the idea of a premium compact similar to Mercedes or Volvo. (They were already partway there.) In those days though most Americans equated price with car size so who knows if that would have flown. Really once GM unveiled the Chevelle and its siblings the jig was up. (Then of course Ford brought out the Mustang and rained on everyone else’s parade for a while.)

AMC nearly went bankrupt in 1967 but managed to talk banksters into extending credit managed to hang in there for another 20 years, albeit with Renault’s funding towards the end. The final nails in the coffin for AMC as an independent company were the 1970s Matador Coupe and Pacer, both of which drained off the company’s scarce development capital and did not even earn back their tooling costs. By the end in 1987 all of AMC’s home-grown passenger cars were based on the 1970 Hornet. (The less said about the Renault Alliance the better. About the only good thing to come out of the hookup with Renault was the Jeep “XJ” Cherokee.)

Jason, YOU using the term “banksters” gives me one helluva chuckle. But you do know your stuff re: Auto Industry history.

Part of the reason AMC even survived in the 60s was its loyal following with the Rambler American, which had its origin with Nash before the 1954 merger with Hudson. Also, there was the acquisition of the Jeep line in 1970 which ended up keeping the company afloat until its acquisition by Chrysler in 1987, the reason indeed why Mopar bought AMC in the first place. When the first “gas crisis” hit late in ’73, the AMC line surged to sudden popularity.

However, the Pacer was what AMC gambled on to replace its failed Ambassador and Matador lines which were supposed to be the profit makers. Between the emissions regs and fuel economy standards, the Javelin was also gone, another profit maker. AMC was hoping to position the Pacer as a “full-sized” compact, and relied heavily on the GM Wankel engine, which ended up not being available. The Pacer had to have the straight six shoehorned in, and it was hard to service and underpowered, and also delivered much worse fuel economy than hoped for. As a documentary on the Pacer put it, once the initial excitement was done and everyone that’d “Bite” had bit, sales flopped. Without cash to refresh their product lines (the AMC Eagle was cobbled from existing parts, but give ’em credit for trying), the company had no choice but to find a partner, and along came the ‘Frogs, looking for a way to get back into the USA market. The AMC/Renault “Alliance” (they even marketed a subcompact with that name) just never got off the ground, and only strong sales of the Jeep line kept the company afloat until a rejuvenated Mopar bought them in 1987.

Banking has always been a dirty, crooked business since the first goldsmith who issued receipts for customers’ stored gold figured out he could issue more receipts than he had gold on hand. “Banksters” is quite appropriate.

Part of the Pacer’s problem was that it became a bloated, overweight turd due to AMC lawyers being concerned about expected federal safety standards. The original design, a fleet, lightweight coupe, was bulked up to meet projected demands by Uncle that actually did not materialize. Given the track record of GM introducing new engine technology at the time it’s probably just as well the GM rotary was never offered. At least the Pacer’s problems did not include a self-destructing engine. The Pacer actually sold well its first year on the market but car buyers quickly found out that it was pathetically slow and guzzled gas nearly as much as a full-sized car of the time. They’re also hell to work on.

I have an Eagle and it’s a pretty remarkable vehicle given AMC’s tiny resources. It was actually a kind of skunk works project pulled off by Roy Lunn and his staff. Management’s reaction when they saw it was What the hell is this? However the company figured they had nothing to lose and might be able to sell a few. Since it cost peanuts to develop although not a huge seller it was profitable and pioneered a new market segment.

The Alliance actually had excellent sales (by AMC standards) the first year. Then word got around about how they would quickly fall apart and sales dropped through the floor. They were extremely crapulent vehicles.

A description of how “modern banking”, based on leveraged credit, was actually well-made, in of all places, a rather dodgy book by William Bramley titled, “The Gods of Eden”. Bramley uses the analogy of a chicken farmer, of good reputation, using promissory notes on his chickens to facilitate exchange, let alone satiate his wife’s constant and infernal *nagging* (ref?) for material comforts in exchange for her “wifely comforts”. Worked nicely as the farmer was a man of integrity, and only wrote a note for a chicken he already had. But once the farmer’s son inherited the farm, with a demanding wifey of his OWN, he soon discovered that only a small portion of notes were redeemed within a given time, SO….

I’d say hang on to that AMC Eagle, it’s the original “crossover” before they became ubiquitous. Along with that relatively bulletproof AMC Six (232 or 258?) and, likely, that “Torque-Command”, also ANOTHER bulletproof auto trans, Chrysler’s Torqueflite. IF that inline six does get “tired”, you might want to consider finding the version put out by AMC’s one-time Mexican subsidiary, VAM, the 282. It did come from THEIR factory with the two-barrel, which it took “Fur-ev-uhr” for AMC to finally put on their USA makes, and IDK if there were any four-barrel versions from the factory, but there are several aftermarket jobs.

Hmm…a FRENCH-designed vehicle falling apart? I’m shocked, shocked I tell you! (your winnings, monsieur). To be fair, those Frogs have made some great stuff as well, the Citroen 2CV being their own post-war “char petit”, which, like the Beetle, was itself a pre-war design on the verge of a mass marketing effort, to be backed up by the French government, and in 1942, Albert Speer actually entered into negotiations with Citroen to produce them as staff and utility vehicles, including a “jeep” version, not unlike the Kubelwagen. That was ‘scotched’ due to, when the Allied “Torch” operation happened in November of ’42, the Germans occupied “Vichy” France, kinda putting it out of business.

Also, the French had actually built some rather, for their time, fearsome tanks, including the Char B1, but aside from it’s tactically-questionable layout, it had an innovative hydraulic steering and levelling system, which tending to crap out at VERY “inopportune” moments in battle. It’s tough enough to handle ANY vehicle when the power steering gives out, let alone a thirty-ton tank.

Morning, Doug!

Another big Pacer problem was overheating… of the passengers. The expansive glass created a kind of greenhouse and if the car did not have AC… and did have the optional Levi jeans seats (with brass rivets)… well. as OJ used to say… look out!

I have a chance once, back in ’85 at post-graduate school in SC, to buy a ’73 Gremlin as a “beater” (wifey #1 and I, expecting a second kid, had just bought one of the new Dodge caravans, 2.5 engine with automatic) with a cherry Levi’s interior; the guy wanted a bit much. In retrospect, the car would’ve been a BARGAIN had I opened the piggy bank and then hung onto it.

Fascinating. When I was little, my parents inherited a Packard, probably late 40s. I remember little about it other than it was green and had a fake-fur lap robe for the passengers in the rear, where there was no heat.

During World War II, American government restrictions on in-house design departments at Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler prevented official work on civilian automobiles. Because Loewy’s firm was independent of the fourth-largest automobile producer in America, no such restrictions applied. This permitted Studebaker to launch the first all-new postwar automobile in 1947, two years ahead of the “Big Three.” His team developed an advanced design featuring flush-front fenders and clean rearward lines. The Loewy staff, headed by Exner, also created the Starlight body, which featured a rear-window system that wrapped 180° around the rear seat.

Above quote is from Wikipedia.

Studebaker’s two-year postwar advantage over GM/Ford/Chrysler in introducing a new model should have been a powerful edge. Most 1946-1948 models from the Big Three were boring warm-overs of their dowdy 1941 tanks.

But somehow Studebaker blew it. Maybe the superior capital resources of the Big Three allowed them to plow under a smaller rival, much as Microsoft used to destroy innovative software companies (Lotus 1-2-3, Word Perfect, Netscape browser) by knocking off their products.

Part of the problem was that there was no need for Studebaker to blow all that money to be “first by far with a postwar car”. Due to pent-up market demand anything with wheels and a motor would be snapped up by car buyers for the first few years after the war. When the Big 3 brought out their new designs for ’49 Studebakers started to look old in comparison and the company did not have the resources for a major redesign.

In fact the last new chassis that Studebaker developed was for their 1953 line designed by Raymond Lowey’s firm. As advanced as the Avanti looked, under the skin it was a 1953 Studebaker down to the kingpins in the front end.

Now THAT’s something that’s got me curious! I wonder what the last Big 3 car to use kingpins? (Ford Econoline vans were probably the last light-duty trucks to have ’em- They used ’em up till around 1990!)

Not sure when other passenger cars abandoned using kingpins. I think most went to ball joints over the course of the 1950s except for AMC which used a trunnion arrangement (kind of like a U-Joint) on the upper front suspension through the 1969 model year.

Jason, bubby, did you write a book on this subject? Your knowledge of this, and the concise yet extremely fact-rich way you state it, and that it seems to flow so effortlessly, while reading so easily, makes me think you must have…or if you haven’t, you need to!

Never knew about those trunnion arrangements….I’ll have to look ’em up!

Nunz, nope, didn’t write any books, but I lived through this stuff. I don’t just look old I am old. 🙂

Reminds me of a T-Shirt I saw another greybeard wearing over the summer: “I’m old, I know things, and I drink.”

You’re only “old” if you’re willing to ADMIT it.

I’m a dirty MIDDLE-AGED man, thank you very much.

Remember what Red Foxx used to say on “Sanford and Son”: “I’ll be a dirty old man ’til I’m a dead old man!” 😉

A fave of my Pop. Back from when HUMOR was allowed.

I doubt we’ll see humor like that on TV ever again. For that matter I’m surprised that youtube has not pulled this clip from the show (yes, any snowflakes and clovers out there, this actually went out over the air on network television):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHWdTjHHXy0

We’d given, via Lend-lease, Chevrolet, Dodge, and Studebaker trucks to the Soviet Union during WWII. It was the Studebaker that one of their companies, GAZ, copied after the war.

Our local car show usually has a handful of Studebakers. I’d contend a crappy Avanti is leaps and bounds more pleasant to drive than anything newly minted. That may well just be cynicism tho.

Hi Mike,

I’ve not yet had the pleasure of driving an Avanti – but I did get close. I was given a chance to drive a Golden Hawk around the block! Whatever these cars’ many flaws, they are so much more engaging – emotionally interesting – than anything new.

Now we need an article about those funky Studebaker pick-ups with the Lark front-end. I’ve only ever seen ONE of those in real life… Used to pass it in the 70’s on the school bus every day, parked at someone’s house…always in the exact same spot. Would pass that same house several times a day in the 90’s when taking cars to the scrapper…and that damn truck was still there, in the exact same spot. Then one day it was gone.

That would be the Studebaker Champ. Take a close look at a photo of one and notice how the truck bed doesn’t really fit with the body. (I’ve heard it described as looking like someone who was wearing an ill-fitting suit.) Studebaker was too broke to tool up for their own bed so they bought the tooling from Dodge for the old Dodge “Sweptline” pickups. Also note the lowered front bumper with no attempt to modify the Lark body’s bumper indentation.

https://img.hmn.com/fit-in/900×506/filters:upscale()/stories/2018/08/597871.jpg

Haha, exactly, Jason! That’s what caught my eye about that truck when I first saw it as a kid- the seemingly mismatched cab and bed! I didn’t even know what it was, then. It was a fleetside too- which made it really obvious. The step-sides are quite as blatant…but still look mismatched. As a kid at the time, I thought somebody had grafted a car front end onto a pick up!.

The International pick-ups were even worse, IMO. While maybe not as mismatched, they were SO fugly, and just didn’t look right. Even as a kid, I always remember wondering why anyone would buy vehicles that were so poorly designed that I could have literally come up with something better. And I guess that was the problem…not enough people did buy them. But that ANYONE bought them boggled my mind…it’s not as if they were 50% cheaper than the Big 3’s…..

****”….the step-sides aren’t quite as blatant….”******